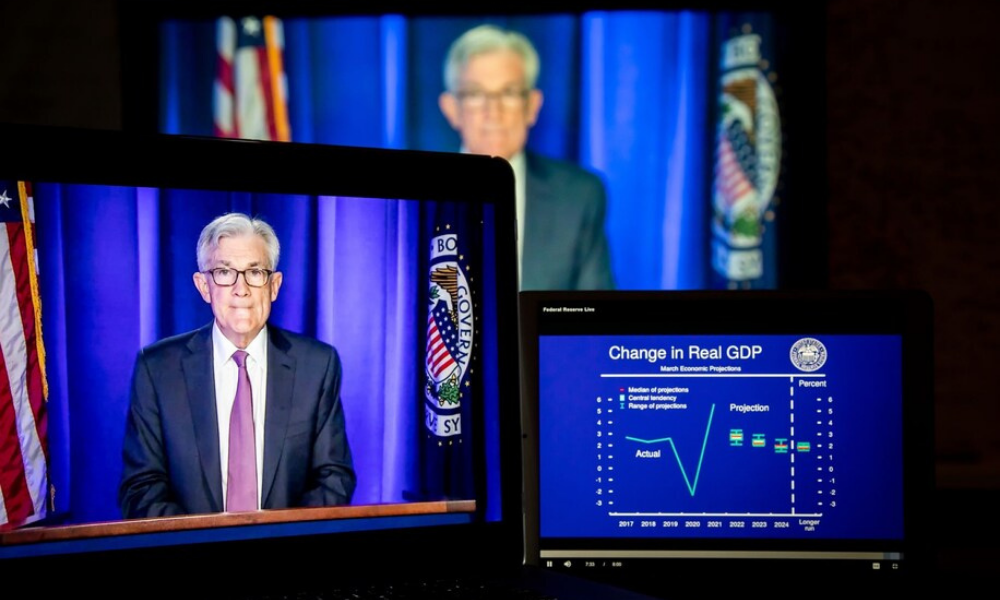

(The Washington Post) - The stock market is drinking the Federal Reserve’s Kool-Aid. On a day when the central bank announced its first interest rate increase since 2018, U.S. equities rallied

Signaling traders believed Chair Jerome Powell when he said the economy was strong enough to survive tighter monetary policy. The argument was compelling if far from bulletproof.

Speaking to reporters after the Fed’s decision to raise rates by a quarter percentage point, Powell said the probability of a recession within the next year was “not particularly elevated” despite the war in Ukraine, higher energy costs, and the increase in rates required to combat the highest inflation in 40 years.

Powell repeatedly pointed to the “strong labor market” and said some of the drivers of inflation should ease later in the year more or less naturally.

Powell isn’t wrong, just optimistic. A recession is an outside possibility this year, but the effects of changes to monetary policy are delayed, and it’s possible that any damage to the economy won’t surface until 2023 or 2024.

| ✅Claimed In 2022 Three Most Effective Trading Indicators For Forex Traders |

A number of scenarios exist in which the U.S. sustains its expansion beyond that, but they require outside factors to go the central bank’s way simultaneously, including lower energy prices, improved global supply chains, and a receding Covid pandemic. None of that is guaranteed.

The Fed isn’t proposing a hands-off approach, of course, and many traders read the central bank’s language as hawkish. In the Fed’s so-called dot plot, the median projection showed the benchmark rate would reach 2.8% in 2023 and remain there in 2024.

Bond yields rose sharply, and the yield curve narrowed as approximated by the gap between 2-year and 10-year Treasury yields. “The Fed has sealed the fate of the yield curve,” wrote Ian Lyngen, head of U.S. rates strategy at BMO Capital Markets.

Some people take inversion of the curve as a sign that recession is becoming more likely. But there’s disagreement on how precisely to measure the curve, and another popular method — three-month and 10-year yields — remains broadly positive.

Overall though, the takeaway seems to be in line with the central bank’s own messaging: The market has seemingly assimilated the idea of rates that are higher than recently expected but not too high to truly knock this economic expansion off course. They might be right about that, but it will probably take a year or so to find out.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners. Jonathan Levin has worked as a Bloomberg journalist in Latin America and the U.S., covering finance, markets, and M&A.

Most recently, he has served as the company’s Miami bureau chief. He is a CFA charterholder.